Introduction

This study guide is a summary of the material covered in lecture thusfar. The Midterm will be focused on both lecture material and assigned readings, but the focus of this guide is the material that we covered in lecture.

The best advice for studying is to focus your attention as much on the "Why?" as the "What?" It's my goal to write an exam that does not depend solely on your ability to memorize terms, definitions, and facts; instead, I'm much more interested in whether you understand why things are the way they are, and in your ability to combine concepts we've learned about in novel ways that we've yet to consider in lecture.

I should point out that this study guide is not intended as a replacement for the lectures or your own notes. It's possible that something we discussed in class will have been left out of the study guide, but is still fair game for the exam. I'm not trying to cheat you on purpose, but the study guide is what it is: it's a guide.

Enjoy.

Background

This course is primarily about software engineering. That the term "software engineering" includes the word "engineering" immediately evokes a few ideas:

- Building things that solve real problems

- Working within real constraints (e.g., How many people do we have? How much time do we have? How much money do we have?)

- Evolving what we build over time, so that it solves new problems

There are many similar definitions of software engineering; one of them is the following:

Software engineering is the application of a systematic, disciplined, quantifiable approach to the development, operation, and maintenance of software.

Some words stand out in that definition:

- Systematic: We're not just going about our process willy-nilly; we have a plan.

- Disciplined: We adhere to our plan and various "best practices" at all times.

- Quantifiable: There are aspects of our development process that we can measure, for the purposes of knowing how well we're doing, how we might improve, and whether our attempted improvements worked.

- Operation and Maintenance: Our work is not done when we ship the first version. We have to keep it running, addressing problems that come up, adding features to solve new problems, and so on.

So when we move out of the realm of programming and into the realm of software engineering is when we scale the sizes of our projects up. It's about programming-in-the-large as opposed to programming-in-the-small. Programming-in-the-large includes some combination of: multiple people, multiple versions, multiple years, multiple related products.

Basic activities in software engineering include:

- Determining the requirements of the system

- Organizing teams to build the system cooperatively

- Defining an overall architecture for the system

- Breaking the larger architecture into modules

- Implementing the individual modules

- Integrating the modules together

- Testing — throughout the process, not just at the end

- Writing documentation

- Configuration management

Process

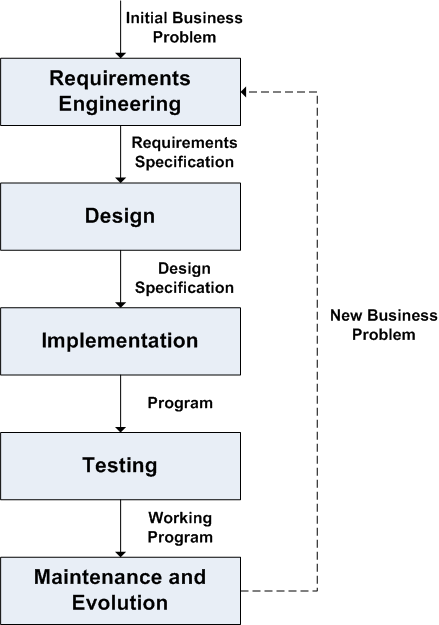

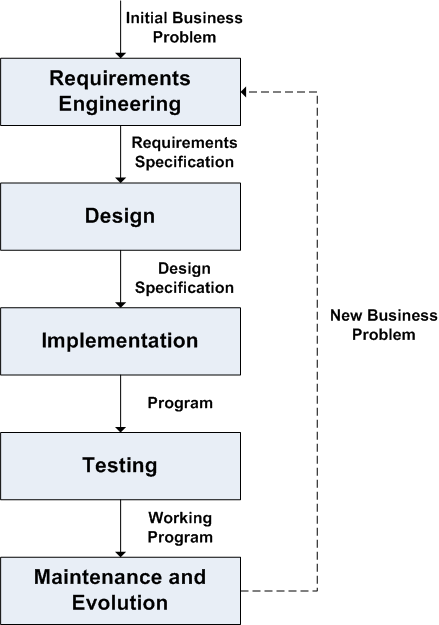

Software is said to go through a lifecycle, in which various activities are done at various points in time. An idealized view of that lifecycle looks something like this:

When embarking on a new software engineering project, we need to decide on a process. In general, a process is a strategy for organizing a project, which answers questions like this:

- In what order will the major tasks be done?

- Who will do the major tasks?

- What information will we exchange with each other as we work?

There is not broad agreement in real-world software development about what process should be used. Virtually anywhere you work will have a process that is at least slightly different than processes you'd use anywhere else. This is partly because software is a relatively young discipline, and partly because different processes work better or worse depending on the situation (e.g., How many people do we have? How much time do we have? How well do our customers understand what needs to be built?).

Processes generally fit into one of a couple of categories:

- Heavyweight or planning-driven processes, in which are careful to plan everything thoroughly before we do it.

- Lightweight or agile processes, in which we accept that things change often, so we spend less time planning and more time building, taking care to work in a way that allows us to change course when we discover that we need to.

There is a spectrum of possible processes, with the most heavyweight on one end and the most lightweight on the other. We discussed the two extremes in lecture: the waterfall model and agile methods.

The Waterfall Model

The waterfall model is one well-known process model for engineering software. It breaks a project into phases, with each phase being one of the activities from the idealized view of the software lifecycle shown above.

Each phase has an output, which is some combination of documentation and code. The output of one phase becomes the input to the next phase. These outputs are depicted in the diagram above:

- Requirements engineering → Requirements specification

- Design → Design specification

- Implementation → Code and program-level documentation

- Testing → Working code and accurate program-level documentation

We can think of the design phase as, itself, being two separate sub-phases:

- Architectural design, which is focused on understanding the major modules and their interactions.

- Detailed design, which is focused on understanding the design of each module's internals (e.g., classes, methods, etc.).

Once we've reached the maintenance and evolution phase, our focus is on keeping the system running and on finding new business problems that could be solved with modifications to the product. As we find new business problems, we can embark on a waterfall-style project in which we make these modifications.

Verification and validation

There are up to two additional tasks we need to perform in each step of the waterfall model: verification and validation (sometimes referred to as V&V). They sound similar, but they're not the same.

- Validation ensures that an attempt has been made to address or implement all of the requirements, so that each part of the program/design can be traced back to a particular requirement. This can be summed up by this question: "Are we building the right system?"

- Verification ensures that each of the requirements is implemented/designed correctly. This can be summed up by this question: "Are we building the system right?"

We don't do both verification and validation at every step. For example, we don't do verification during requirements engineering, since we haven't designed or implemented anything yet.

Testing and the V-model

Testing is incorporated throughout a waterfall process — as it should be throughout any process. Test plans are part of the output of each phase, describing testing that will need to be done subsequently.

- Requirements engineering → Acceptance test plan

- Architectural design → Integration test plan

- Detailed design → Unit test plan

One way to represent this relationship pictorially is often called the V-model, which depicts the waterfall model, along with related forms of testing that are planned early on and them performed later.

Assessment of the waterfall model

The waterfall model works beautifully in an ideal world where we always complete each phase correctly the first time. In reality, of course, we don't, so we need a way to backtrack to previous steps if necessary. The cost of that backtracking is higher the further back we have to go; for example, discovering an incorrect requirement during the testing phase requires us to revisit the requirements specification, the design documentation, and the program, along with the relevant test plans.

Not surprisingly, the waterfall model has significant downsides in practice.

- It is assumed that we'll have perfect information available and that we'll perform perfectly at each step. The customers will know exactly what they want during the requirements engineering phase; the designers will anticipate all possible problems during the design phase; the implementers won't make any mistakes during the implementation phase; and the testers won't miss any problems during the testing phase.

- The later we discover a bug, the more expensive it is to fix, because we have more phases to revisit, more documentation to alter, and more people involved.

- Because of the need to backtrack, we'll often be working on multiple phases simultaneously, which makes it difficult to track progress; at any given time, we might not be done with any of the phases, even though we're working on all of them!

Agile methods

The waterfall model represents one extreme along a spectrum of software development processes, one where planning is king and we don't act until we know exactly where we're going. The opposite extreme is a set of processes called agile methods. Agile methods arise from the basic idea that change is inevitable, because:

- ...mistakes are made throughout the process, which need to be cleaned up.

- ...we don't always have perfect information available when we make decisions.

- ...customers change their minds about what they need all the time.

- ...customers' actual needs really do change (e.g., business processes are altered as the organization grows, applicable laws change).

There are a number of variants of agile methods (e.g., Extreme Programming, Scrum), though they are generally all built according to the same set of principles. These principles are laid out in a document called the Manifesto for Agile Software Development (also known as the Agile Manifesto), the most important part of which reads as follows:

We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it. Through this work we have come to value:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more.

Agile methods have the following properties:

- They involve the customer throughout the process. A central tenet is that at least one customer representative is a full-fledged member of the team.

- They build complete, working subsets of the system — as often as every few weeks, in many cases. While the subsets are obviously incomplete, actual requirements are addressed correctly in each iteration.

- They focus on people and their interactions. Teams often work together in one large room to facilitate interactions. (Pair programming, in the sense that you've used in prior coursework, is often used.)

- They encourage looking out "code smells" and refactoring as soon as those smells develop. For example, duplicate code is eliminated when found, poor design choices are revisited as soon as it's clear they can be improved, and so on.

- They require testing throughout the process, with as much of that testing automated as possible.

- They don't generate as much documentation as heavyweight processes. Requirements are often written on index cards or some electronic equivalent; the code and tests, in general, are the documentation. If you want to know how something works, look at its code and, as importantly, its tests.

Extreme Programming

Extreme Programming (XP) is an example of an agile method. It is centered around a set of practices, some of which are:

- Small releases: Each version is not much different from the one that preceded it.

- The planning game: Determining the scope of the next release is done quickly. Rather than attempting to define everything we need to do, we just develop a small list of things we know we need to do.

- Simple design: Creativity and "cleverness" are frowned upon. Simpler and clearer is always considered better.

- Testing: Unit tests are written for all code that will make up the product.

- Refactoring: The design is changed when necessary, without affecting its behavior. This refactoring is automated whenever possible.

- Pair programming: All code that makes up the product is written in pairs, to reduce the probability of mistakes.

- Collective ownership: Anyone can change anything at any given time.

- 40-hour week: Long weeks are the exception rather than the rule, since long weeks tend to lead to tired developers, which leads to mistakes that will be expensive to fix later.

- On-site customer: A customer representative is a full-fledged memnber of the team, available at all times.

Software Quality

We'd like to build quality software. But what is software quality? What should we be shooting for? Quality software...

- ...meets its requirements (i.e., solves a business problem).

- ...is user friendly, if it has a user interface at all.

- ...is safe (i.e., it won't harm people or property).

- ...runs on available hardware.

- ...and so on.

Measuring quality empirically is a difficult proposition; despite much work in this area over the last few decades, there are not measurements that can automate the process of deciding whether you have achieved quality.

This doesn't mean that there aren't attributes that quality software tends to have. We should know how to recognize these attributes and use them as guidelines as we work.

- Correctness: Does the system meet its requirements and fulfill its objectives?

- Reliability: Does the system work at all times, or does it suffer from frequent bugs?

- Efficiency: Does the system require a reasonable amount of resources (i.e., time, memory, processing power, energy).

- Security: Does the system prevent unauthorized users from accessing information they shouldn't? Does it allow users to access information they should be able to see?

- Usability: Is it possible to learn how to use the system in a relatively short amount of time? Is it possible to perform tasks with a minimal amount of effort?

- Maintainability: Is it simple to locate and fix bugs in the system?

- Flexibility: Is it possible to modify the system easily, so that it can be adapted to new requirements?

- Testability: How difficult is it to test the system?

- Portability: Is it easy to move the system from one operating environment (i.e., hardware, operating system) to another?

- Reusability: Can parts of the system be reused in others?

- Interoperability: Can the system be integrated easily with other systems?

- Fault tolerance: How well does the system survive bugs and other problems?

- Safety: Does the software harm people, organizations, software, property, or the environment?

Some of these factors trade off of others (e.g., sometimes efficiency harms maintainability, testability, and reusability).

Requirements Engineering

Requirements engineering is the process of analyzing a customer's problem, gaining an understanding of what a system could do to solve it, documenting that understanding, and checking the accuracy of that understanding. The product generated by requirements engineering is called a requirements specification; it details the current understanding of what the requirements for a system are.

First of all, we should decide what is meant by a requirement. A requirement is "a condition or capability needed by a user to solve a problem or achieve an objective." It's something that the system should be able to do, or a constraint that the system must meet. Requirements are not necessary "musts" in a system; many requirements are, in practice, negotiable.

The requirements engineering process is characterized at least partly by the need to address the concerns of many stakeholders. A stakeholder is anyone that is concerned with the system in some way:

- Developers who will build the system

- Testers who will ensure that the system meets its specifications

- End-users who will use the system after it's completed

- Managers of end-users who are responsible for their work

- Regulators who will ensure that the system meets any legal requirements

- Domain experts who give essential background information about the application domain

Different stakeholders bring different kinds of requirements to the table. Those requirements can even conflict. For example, YouTube has a requirement that people be allowed to upload videos; ideally, they can upload any video they'd like. Copyright holders, however, view this requirement differently.

Requirements engineering is comprised of four tasks:

- Requirements elicitation, during which we interact with users, customers, etc., to gain an understanding of what the requirements should be.

- Requirements specification, during which we write up what our understanding is.

- Requirements validation and verification, during which we and our customers agree upon that understanding.

- Requirements negotiation, during which we negotiate with the various stakeholders when there are requirements that conflict.

Requirements elicitation

A variety of techniques can be used to elicit requirements, including interviews, brainstorming, surveys/questionnaires, task analysis, ethnography, and prototyping. We choose these techniques based on who we need to interact with and what we need to know.

Requirements specification

A requirements specification is a document that describes the complete set of known requirements for a software engineering project. A good requirements specification has several attributes:

- Correct: Of course, first and foremost, we want the specification to reflect the actual needs of the users.

- Unambiguous: We should choose the clearest, least-ambiguous language possible. This is difficult when writing in a natural language like English — natural languages are inherently ambiguous. While there are formal languages that can be used to write requirements (e.g., Z), they are not in wide use.

- Complete: We should include every requirement discussed. Those that have been negotiated out might still be included in a "future directions" section.

- Consistent: There should not be requirements that conflict.

- Prioritized: The requirements should be prioritized so that it is clear which are more important than others. (E.g., "must have," "should have," "could have," "won't have.")

- Verifiable/testable: It should be possible to verify that a requirement can be met. We need to be specific.

- Modifiable: It should be easy to make changes to the specification. Some of the same techniques that make it easier to modify code apply here, as well: avoiding duplication of information, categorization and organization.

- Traceable: It should be possible to trace requirements forward and backward, so we should given them unique identifiers and use those identifiers elsewhere in our process.

When writing a requirements specification, we want to focus on the "what" and not the "how." For example, we want to avoid implementation bias whenever possible. If we're building a web-based system, the underlying technology we choose (e.g., Java EE, PHP, .NET/ASP) is essentially irrelevant. Either way, a web site is a web site.

Kinds of requirements

We can categorize requirements in many ways. One way we did so in lecture was to separate them into functional and non-functional requirements.

- Functional requirements define the specific behavior of the system.

- Non-functional requirements define additional requirements other than what behavior the system supports (e.g., performance, security, cost, usability, etc.).

Acceptance test plans

Part of the requirements engineering process is to draw up an acceptance test plan, which details how a system will be tested to ensure that it is acceptable to the customer. Various scenarios will be described — in relatively open-ended terms, since we want to avoid implementation bias — the successful completion of which indicates that the system is ready to be delivered.

Design

Once requirements are agreed upon, it's time to begin working on a design for your system. Design is a many-faceted task, whose complexity rises substantially with the complexity of the system being developed. There is no one "right way" to design software, but there are many well-understood lessons and "best practices," recurring problems for which well-known solution patterns are known, and qualities that we know that good designs generally have and that bad designs generally lack.

We can say that design comes in two flavors: architectural design, which focuses on the "big picture"; and module design, which focuses on details like classes, methods, and so on.

There are a number of goals we're trying to achieve during the design phase:

- Decomposing the problem into modules

- Deciding on architectures for arranging these modules

- Developing a plan for how the team will work on these modules

- Estimating cost

- Determining what external systems we'll need to interface with and how we'll do it

- Visualizing the intangibles (using modeling, diagrams, etc.)

Moduality

Software is generally built by many people and generally has many versions over its lifetime; both of these facts pose issues that we'll need to solve. The solution to both is modularity; we should pefer to decompose our system into a collection of subsystems.

Good modules have at least three characteristics:

- High cohesion. All internal parts are closely related.

- Low coupling. Modules rely on each other as little as possible.

- Information hiding. Modules hide design and implementation decisions. (By "hiding," I mean that other modules have no way of depending on these decisions. If they can't depend on these decisions, we can change our minds without breaking these other modules.)

Qualities of a good design

It's hard to define precisely what a "good" design is, but we do know that there are some desirable qualities that good designs have.

- Rigor. All requirements are addressed.

- Separation of concerns. Modules each solve a single problem. They can be written and tested independently.

- Anticipation of change. It should be possible to inject new functionality into a module with minimal impact.

- Incrementality. It should be possible to work on the software in a piecemeal fashion, as opposed to having to build many pieces before being able to test any of them.

UML

The Unified Modeling Language (UML) is a collection of kinds of diagrams that we can use to describe the design of a software system. Different diagrams address different parts of our design. We spent a fair amount of time talking about one of these diagrams: UML Class Diagrams. The discussion slides on this topic show the various notations used in UML Class Diagrams.

Use cases

Another way to view a design is in terms of problems that the system will need to solve and scenarios in which the system will be used to solve them. Use cases are a way of describing the behavior of a system from the points of view of a set of actors. Actors are entities external to the system (e.g., human users, other automated systems). Use cases are described as a sequence of events, in which an actor interacts with the system in some way.

Use cases are focused on goals: what is each actor trying to achieve and how can the system help them to achieve it? We define details like user interface only to the extent that we can describe a scenario; the use cases will eventually be used when we consider a more detailed view of our design (e.g., user interface design, module design).

There are many arrangements of use cases. One such arrangement has use cases broken up into the following sections.

- Name. We give the use case a name (and a short identifier) that describes it.

- Requirements Addressed. What requirements are addressed by this use case?

- Goal. What are the actors going to try to achieve in the case described?

- Brief Description. What is going on in this use case?

- Actors. What actors are involved?

- Preconditions. What must be true before this use case can be executed?

- Triggers. What forces cause the use case to be executed? Is it a user wanting to do something? Is it something that happens at a repeating interval (e.g., once per hour)?

- Sequence of Events. A description of sequence of events that will lead to the goal being achieved.

- Postconditions. What will be true after the use case has been executed?

An example use case, which we wrote in lecture, follows.

- Name: Adding a Student to the System

- Requirements Addressed: ST-2

- Goal: To add a new student when they arrive for their first interim counseling meeting.

- Brief Description: Students are not automatically entered into the system. So, when a student arrives for his or her first interim counseling meeting, CCO Counselors will need to gather identifying information from the student and enter it into the system, so that the student can subsequently be scheduled into courses.

- Actors: CCO Counselor, Student

- Preconditions: Student has not enrolled in classes at the university previously.

- Triggers: Student arrives for first-ever counseling appointment.

- Sequence of Events:

- Student arrives at CCO for meeting with CCO Counselor.

- Student provides student ID to CCO Counselor.

- CCO Counselor logs into system.

- CCO Counselor looks up student by ID and determines that student is new.

- CCO Counselor asks Student for identifying information (see requirement ST-1).

- CCO Counselor enters identifying information about Student into system.

- CCO Counselor saves changes.

- Postconditions: Student's information will be stored in system.

Architectural styles

As we start to attack larger-scale problems, it becomes more difficult to discover a methodology for arranging our modules and their interactions. Luckily, there are kinds of problems that recur, for which good architectural solutions have been designed and have proven useful. These solutions are called architectural styles. Architectural styles represent "success stories" from the work of previous designers; to understand and use them, when appropriate, is to avoid going through the process of trial-and-error that those previous designers endured in order to find their design.

Some well-known architectural styles:

- Hierarchy, or Main program with subroutines, in which the set of modules and their relationships (i.e., who calls who) form a hierarchy. This is a useful style to use when writing a single program, though a lot of interesting software is built out of a collection of programs.

- Abstract data type. An abstract data type (ADT) is a set of data and a set of operations for safely manipulating that data. ADTs, in a sense, allow us to extend our programming language, by implementing concepts that are not built into the language (as int or boolean types might be), then having them available to us throughout our system.

- Examples include a DateTime class that represents a point in time, a TimeSpan class that represents a duration of time, and a Money class that represents currency.

- Implicit invocation. Modules communicate with other modules by sending "signals," but the sending modules are not aware of who the receivers are. There is sometimes what we call a "bus" that is used to carry the signals from one module to another. This is a style that can lead to a very flexible design, because we can mix and match components more easily.

- This is the way that GUIs work in Java; the components, such as buttons, react when clicked by calling a method on a set of "listeners," who are objects interested in knowing when the button is clicked. The button's implementation does not depend on who the listeners are, but onl the mechanism for how to notify them.

- Client-server. Connections between modules are remote procedure calls, meaning that they are done across a network (hence the word "remote") but otherwise are a lot like procedure calls (i.e., parameters are passed, a result is returned). There is an explicit distinction between a server (a module that provides a service) and a client (a consumer of that service).

- Web browsers interact with web servers this way. Browsers send a particularly-formatted request and servers send back particularly-formatted responses.

- Repository or Blackboard. A central repository, or database, holds data. Modules "surround" the repository and share its data. As changes are made by one module, they are published to the repository; those changes can then be picked up (or "pushed" to) other modules.

- This style is extremely common in lots of "real" systems, where databases are extremely common. (Examples include web sites with dynamic content, "enterprise" systems, and source control systems.)

- Peer-to-peer. An increasingly common approach to solving certain kinds of problems is for modules to interact (generally across a network), but for none of them to be anointed as "clients" or "servers." Instead, all are peers, meaning that they have equal rights and responsibilities. The peers exchange information in a systematic fashion, collaborating on trying to solve some kind of problem.

- BitTorrent, which is a peer-to-peer protocol for sharing files amongst many people (by splitting the file into many smaller chunks and having the peers "trade" for chunks that they don't already have), is a great example of this.

- Pipes and filters. A series of independent, sequential transformations are made to data. The output of one module is the input to the next module. The modules have little or no state of their own; they simply know how to take what's given to them and affect some kind of change on it. In this approach, we call the modules filters and the connections between those modules pipes.

- This approach can lead to very flexible architectures, in which the output of the system is radically changed simply by rearranging the filters (e.g., adding one, removing one, or changing their order).

- Layered. Modules are arranged into layers. Modules in one layer only use modules in the layer directly below them. You could say that each layer hides the details of how the layers below it work. Layers are a good way of preventing particular complexities from pervading very far into a system; a detail is handled in one layer, hidden away in that layer so that no other layers need to know about it.

- Networks are almost always implemented this way. There are different arrangements of layers that are used in practiced, but layered architectures are ubiquitous.

It is not necessarily the case that there is one architectural style for a whole project. We often combine them together.